You might be familiar with Linux load averages already. Load averages are the three numbers shown with the uptime and top commands - they look like this:

load average: 0.09, 0.05, 0.01

Most people have an inkling of what the load averages mean: the three numbers represent averages over progressively longer periods of time (one, five, and fifteen-minute averages), and that lower numbers are better. Higher numbers represent a problem or an overloaded machine. But, what's the threshold? What constitutes "good" and "bad" load average values? When should you be concerned over a load average value, and when should you scramble to fix it ASAP?

First, a little background on what the load average values mean. We'll start out with the simplest case: a machine with one single-core processor.

The traffic analogy

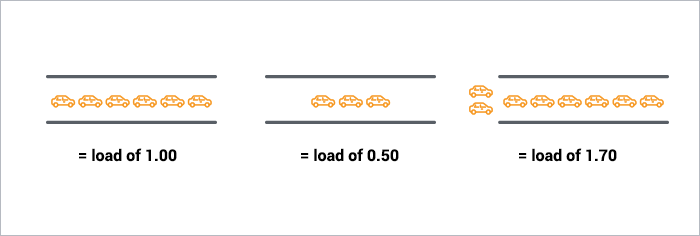

A single-core CPU is like a single lane of traffic. Imagine you are a bridge operator ... sometimes your bridge is so busy there are cars lined up to cross. You want to let folks know how traffic is moving on your bridge. A decent metric would be how many cars are waiting at a particular time. If no cars are waiting, incoming drivers know they can drive across right away. If cars are backed up, drivers know they're in for delays.

So, Bridge Operator, what numbering system are you going to use? How about:

- 0.00 means there's no traffic on the bridge at all. In fact, between 0.00 and 1.00 means there's no backup, and an arriving car will just go right on.

- 1.00 means the bridge is exactly at capacity. All is still good, but if traffic gets a little heavier, things are going to slow down.

- over 1.00 means there's backup. How much? Well, 2.00 means that there are two lanes worth of cars total -- one lane's worth on the bridge, and one lane's worth waiting. 3.00 means there are three lanes worth total -- one lane's worth on the bridge, and two lanes' worth waiting. Etc.

This is basically what CPU load is. "Cars" are processes using a slice of CPU time ("crossing the bridge") or queued up to use the CPU. Unix refers to this as the run-queue length: the sum of the number of processes that are currently running plus the number that are waiting (queued) to run.

Like the bridge operator, you'd like your cars/processes to never be waiting. So, your CPU load should ideally stay below 1.00. Also, like the bridge operator, you are still ok if you get some temporary spikes above 1.00 ... but when you're consistently above 1.00, you need to worry.

So you're saying the ideal load is 1.00?

Well, not exactly. The problem with a load of 1.00 is that you have no headroom. In practice, many sysadmins will draw a line at 0.70:

- The "Need to Look into it" Rule of Thumb: 0.70 If your load average is staying above > 0.70, it's time to investigate before things get worse.

- The "Fix this now" Rule of Thumb: 1.00. If your load average stays above 1.00, find the problem and fix it now. Otherwise, you're going to get woken up in the middle of the night, and it's not going to be fun.

- The "Arrgh, it's 3 AM WTF?" Rule of Thumb: 5.0. If your load average is above 5.00, you could be in serious trouble, your box is either hanging or slowing way down, and this will (inexplicably) happen in the worst possible time like in the middle of the night or when you're presenting at a conference. Don't let it get there.

What about Multi-processors? My load says 3.00, but things are running fine!

Got a quad-processor system? It's still healthy with a load of 3.00.

On a multi-processor system, the load is relative to the number of processor cores available. The "100% utilization" mark is 1.00 on a single-core system, 2.00, on a dual-core, 4.00 on a quad-core, etc.

If we go back to the bridge analogy, the "1.00" really means "one lane's worth of traffic". On a one-lane bridge, that means it's filled up. On a two-lane bridge, a load of 1.00 means it's at 50% capacity -- only one lane is full, so there's another whole lane that can be filled.

Same with CPUs: a load of 1.00 is 100% CPU utilization on a single-core box. On a dual-core box, a load of 2.00 is 100% CPU utilization.

Multicore vs. multiprocessor

While we're on the topic, let's talk about multicore vs. multiprocessor. For performance purposes, is a machine with a single dual-core processor basically equivalent to a machine with two processors with one core each? Yes. Roughly. There are lots of subtleties here concerning amount of cache, frequency of process hand-offs between processors, etc. Despite those finer points, for the purposes of sizing up the CPU load value, the total number of cores is what matters, regardless of how many physical processors those cores are spread across.

Which leads us to two new Rules of Thumb:

- The "number of cores = max load" Rule of Thumb: on a multicore system, your load should not exceed the number of cores available.

- The "cores is cores" Rule of Thumb: How the cores are spread out over CPUs doesn't matter. Two quad-cores == four dual-cores == eight single-cores. It's all eight cores for these purposes.

Bringing It Home

Let's take a look at the load averages output from uptime:

~ $ uptime23:05 up 14 days, 6:08, 7 users, load averages: 0.65 0.42 0.36

This is on a dual-core CPU, so we've got lots of headroom. I won't even think about it until load gets and stays above 1.7 or so.

Now, what about those three numbers? 0.65 is the average over the last minute, 0.42 is the average over the last five minutes, and 0.36 is the average over the last 15 minutes. Which brings us to the question:

Which average should I be observing? One, five, or 15 minutes?

For the numbers we've talked about (1.00 = fix it now, etc), you should be looking at the five or 15-minute averages. Frankly, if your box spikes above 1.0 on the one-minute average, you're still fine. It's when the 15-minute average goes north of 1.0 and stays there that you need to snap to. (obviously, as we've learned, adjust these numbers to the number of processor cores your system has).

So # of cores is important to interpreting load averages ... how do I know how many cores my system has?

cat /proc/cpuinfo to get info on each processor in your system. Note: not available on OSX, Google for alternatives. To get just a count, run it through grep and word count: grep 'model name' /proc/cpuinfo | wc -l

More servers? Or faster code?

Adding servers can be a band-aid for slow code. Scout APM helps you find and fix your inefficient and costly code. We automatically identify N+1 SQL calls, memory bloat, and other code-related issues so you can spend less time debugging and more time programming.

Ready to optimize your site? Sign up for a free trial.

More Reading

- Wikipedia - A good, brief explanation of Load Average; it goes a bit deeper into the mathematics

- Linux Journal - very well-written article, goes deeper than either this post or the wikipedia entry.

More on Linux Performance

Subscribe to our RSS feed or follow us on Twitter for more insight on Linux performance.