Overview

Python powers many applications we use in our day-to-day like Reddit, Instagram, Dropbox, and Spotify. The adoption of Python 3 has been a subject of debate in the Python community. While Python 3 has been out for more than a decade now, there wasn’t much incentive to migrate from the stable Python 2.7 in the earlier releases.

If you’re still running on legacy python, it’s high time to migrate as it has reached the end of its life since Jan 2020. If that is not enough motivation or you have too much in place for Python 2.7 in your code, read on.

In this article, we’ll discuss —

- Why should you care about the migration to Python 3?

- New and lucrative features of Python 3 which can take performance and developer productivity significantly up

- Concrete steps and strategies you could follow if you were to migrate a vast code-base running on Python 2

- Automated tools to help migrate — 2 to 3, Python-Future and Modernize with examples

- Learning the process through the migration stories of Instagram, Dropbox, and Facebook, which are running Python 3 on the scale of a billion users.

Why invest in upgrading from Python 2 to 3?

“I think Python 3 is actually is a better programming language than Python 2 was. I think that it resolves a lot of inconsistencies” — Glyph Lefkowitz, founder of Twisted — a popular networking engine written in Python

Python 2.7 was an LTS(long term support) release of Python, so most of the users didn’t have to worry about porting their code every 18 months, which could be a considerable investment. Moreover, the migration process isn’t very straightforward, especially for the bigger code-bases where no single person has the context of all the parts of the software.

Tools and packages cannot fully automate the process; one has to intervene at some places manually. The manual piece is why it is good to understand unit test coverage so you can identify the input and expected output from a function and refactor it with assurance.

That said, here are two critical reasons why an investment in migration could be productive for you —

Developer Productivity

One of the big reasons for Python’s popularity is that it is easy to learn and write. It is dynamically typed and doesn’t enforce strict type checking. This can become complicated as your code scales. Let’s check out an example.

def get_category_id_from_cities(name, cities_map):

"""

Input:

name - (str)

cities_map - (dict)

Returns:

category_id - (int)

"""

This is a simple function that takes in two arguments, does some operation, and returns an output. There’s a beautiful doc string added by the developer, which tells you the type of parameters it is expecting and the return type.

However, this piece of function is hard to scale. Without a standard type system in place, it is easy to introduce new inputs arguments, modify the types and comment can quickly go out of sync with the implementation over time.

Most of the teams facing this issue use a popular python package mypy for optional type checking. Python 3.5 introduced type annotations(PEP 484) as a standard system for the same.

The above piece of function would look like this with type hints —

from typing import Dict

def get_category_id_from_cities(name: str, cities_map: Dict[str, int]) -> int:

# Do something

pass

These type hints are entirely optional, i.e., they do not enforce static type checking and are ignored at runtime. Including them into your code makes it self-documenting, easy to understand, and modify. This, in turn, increases developer velocity. We’ll discuss type annotations in detail in the next section.

Performance Improvements

Here’s a screenshot from speed.python.org, which is an official performance benchmarking tool for Python. This graph lists some everyday application operations on different Python versions.

You’ll realize that Python 3.7 and 3.8 are fastest yet for almost all operations except for startup time than Python 2.7. For most applications, a few millisecond difference in startup time wouldn’t matter.

Python 3 has improved on many CPython implementations over time, moved, and re-implemented standard library capabilities in C, giving a significant performance boost to standard utilities.

More than these general improvements, Python 3 introduced the asyncio module in 3.4 release, which enables asynchronous programming. What it simply means is that while your current request is waiting on an I/O operation, you can use that time to serve another request.

With all this in mind, the debate of Python 2 vs. 3 can be solved by merely saying after the migration; your code would use half the memory and run twice as fast. According to Instagram’s Pycon 2017 Keynote, after moving to Python 3, they reported a 12% CPU and 30% memory utilization win on their uwsgi/Django and Celery(async) tier, respectively.

Python community is moving continuously towards improving 3; there’s no good reason to stay on 2 now, the delay in migration is the delay on missing out substantial performance improvements and excellent new features. One of the most popular frameworks — Django, has dropped the support of Python 2 entirely(Django 2.0), and here’s a full list of projects which have pledged for dropping support of Python 2 from 2020.

What’s new in Python 3?

This section details some of the new features introduced in Python 3(aggregated till 3.8) with examples. Most of the syntax and type changes can be taken care of by using automated tools like 2 to 3, modernize, etc. discussed in the next section. However, there are some traps, especially when handling strings, which might require you to understand the code before making the compatible change.

Changes to Core Types

Understanding the new Strings

One of the significant incompatible changes in the way strings are now handled in Python 3, and you’ll probably spend most time fixing lines in your Python 2 code.

Let’s first understand the two uses or types of strings —

Text or normal strings — the human-readable form used to display a sequence of characters on a webpage or application. It can have of characters, currency symbols, emojis, alphabets from different languages, and so on.

Data or Bytes Data: Machines can process the binary encoding of normal strings. A sequence of bits that is used while writing data to the disk, or transmitting it over a network.

Unicode

Let’s talk a bit about Unicode. Unicode is an attempt to map every character or symbol known to humans to a codepoint. It is not an encoding. A codepoint is a value given to a character that can then be encoded to binary using any encoding scheme like UTF-8, UTF-16, etc. These values, according to Unicode are written as hexadecimal numbers prefixed with U+ (Ex U+0041 = A).

Now in Python 2, a single type str was used to represent the text as well as binary data. Default encoding was 7-bit ASCII. If you needed to support Unicode characters, there was a separate type for it called unicode. Python 2 allows the mixing of these two different types by implicitly casting the strings, but it’d cause problems at runtime.

In Python 3, str and bytes types are explicitly different, and the mixing of these is not allowed. unicode Type in Python 2 corresponds to str type in Python 3. All the string literals in Python 3 are now Unicode, be it single, double, or triple quote docstrings. Also, UTF-8 is default encoding in Python 3.

Here are some simple examples of string concatenation differences in Python 2.7 and 3.7. Notice that we can use encode() and decode() functions to handle the type conversion specifically.

Let’s see one more example of how Python 2 handles non-ASCII characters and how to avoid a common pitfall of string manipulation.

In the above example, when we try to format a non-ASCII character(£) in the second step, Python 2 garbles it to hexadecimal value, while Python 3 can handle it perfectly fine.

When you try to convert it to a Unicode string on the next step for fixing, you see the dreaded UnicodeDecodeError. You’d be hitting it very often if your application is playing with strings. The simple solution is to use literal u in front of every such string. The automatic tools for conversion discussed later will mostly take care of this for you.

File I/O

In Python 2, file opened using open() is being read as general str type. While in Python 3, you have to specify the mode to open the file. The default is the text type. It is a common pitfall as now you cannot treat the files which are not encoded using UTF-8(PNG, JPG etc.) and expect them to be read as Unicode text.

Changes to the Dictionary type

There have been three significant changes to dictionaries in Python 3. Let’s explore them one by one.

Views/Iterators instead of lists

The support of functions iteritems(), iterkeys() and itervalues() has been removed and now items(), keys() and values() return views instead of lists.

Checking the existence of a key in dict

dict.has_key() is no more. It has been removed in support of in operator. Whether a key exists in a dict or not can be checked by key in my_dict.

Ordering of keys in a dict

In Python 2, the order of elements in a dictionary remained the same with every execution. This exposed a security vulnerability in Python 2(CVE-2012-1150) for DOS(Denial of Service) attacks as you could predict the order of elements.

Your code could be relying on this behavior of Python 2. Python 2.6.8 introduced an environment variable $PYTHONHASHSEED which when set to random, overcomes this security vulnerability by randomizing the hash function. This behavior is on by default beyond Python 3.3.

In Python 3.6, dictionaries were re-implemented to consume 20–25% less memory than Python 3.5 and suggested that keys will be preserved by their insertion order. However, this behavior can only be relied upon beyond Python 3.7.

Changes to the Numeric Types

long and int type

long type in Python 2 has been renamed to int in Python 3. int will handle the large values automatically. In Python 2, if the int overflowed because of some operation, it was implicitly converted to long type.

If your application contains the code which relies on the distinction of int and long from Python 2, it’ll need to be fixed. Automatic conversions won’t be able to take care of this logic.

Division / Operator

In Python 2, / operator returned the floor value while dividing two integers and a float if any of the operands is float. Python 3 returns float value in both cases.

There are no changes to the behavior of floor // division operator. So, you could change your Python 2 code to use // where floor division is specifically required.

New Modules and STL Re-organization

This section covers some new and interesting things introduced in Python 3.

f-strings(PEP 498)

f-strings are a lot cleaner and easier way to format strings than the traditional %formatting or the str.format() function. Stating from the documentation of PEP-498 —

F-strings provide a way to embed expressions inside string literals, using a minimal syntax. It should be noted that an f-string is really an expression evaluated at run time, not a constant value. In Python source code, an f-string is a literal string, prefixed with ‘f’, which contains expressions inside braces. The expressions are replaced with their values.

Also, f-strings are faster than both traditional formatting approaches. Since it’s a way to embed all kinds of python expressions, you can make function calls within the string. Let’s see f-strings in action with some examples —

Python 3.7

>>> # Expression evaluations

>>> name = "Google"

>>> f"You could {name} this."

'You could Google this.'

>>> f"{5 * 5}"

'25'

>>> # function call within string

>>> name = "GOOGLE"

>>> f"You could {name.lower()}"

'You could google'

>>> # Multiline formatting example

>>> name_1 = "Google"

>>> name_2 = "Microsoft"

>>> name_3 = "Facebook"

>>>

>>> (f"Here's some top "

... f"tech companies of "

... f"the world - {name_1}, "

... f"{name_2} and {name_3}.") # Note that there's an 'f' in front of every line

"Here's some top tech companies of the world - Google, Microsoft and Facebook."

f-string usage examples

f-strings also allow specifying the conversion type with !r, !s and !a which call the repr(), str() and ascii() on the expression. Here’s a simple example of the same —

class Avengers(object):

def __init__(self, superhero_name, actual_name):

self.superhero_name = superhero_name

self.actual_name = actual_name

def __repr__(self):

return f"{self.actual_name} is the {self.superhero_name}"

>>> ironman = Avengers("Ironman", "Tony Stark")

>>> f"ironman!r"

>>> 'Tony Stark is the ironman'

f-string type conversion example

Type Hints(Type Annotations)

Type Hints were introduced with typing module in PEP 484. We’ve already talked about what type hints are and their benefits in the long run. They make refactors easier by preventing common bugs, improve the readability of code, and promote IntelliSense(Intelligent code completion).

Type Annotations are invaluable additions that require some extra development efforts in the beginning, just like documentation and writing tests, but are justified in the long run.

Let’s take a look at some primary type hinting examples from this gist. There are comments to explain the different cases.

# 1. The hello world of type hinting

def greeting(name: str) -> str:

return f"Hello {name}"

# 2. Type hinting a complex type

from typing import Dict, List

class Node:

pass

def get_node(node_map: Dict[str, List[Node]]):

# Do something

# 3. Type Aliases

from typing import Tuple

Node = Tuple[int, str]

def pop_node(node: Node) -> Node:

pass

# 4. Type hinting Callables can be done by using Callable[[arg_1, arg_2, arg_X], ReturnType]

from typing import Callable

def async_query(on_success: Callable[[int, str], str],

on_failure: Callable[[int, str], None]):

pass

# 5. You could use Any as a special type assignable to and from any type.

# Similarly None can be used for specifying type(None)

from typing import Any

def delete_elements(list: List[Any]) -> None:

pass

Some important things to note about type hints —

- There’s no type checking at runtime, and type hints are not mandatory. Python remains a dynamically typed language. You could pass an

intto a function expectingstrand shoot yourself in the foot. Then what’s the use? - You could use mypy or implement runtime type checking functionality in your code by using decorators or metaclasses. The

typingmodule providesget_type_hints()function for the same. This is especially helpful for IDEs(Pycharm, VS Code), which can improve their IntelliSense based on type hints. - If you change the implementation of the function without changing types in its comments, nothing happens. But, with type checkers or linters in place, if you don’t change the type hints, they will probably yell at you.

Asyncio(Asynchronous I/O)

Introduced in PEP 3156, asyncio is a way to write concurrent code using the async/await syntax. Let’s talk a bit about why it is needed.

Network I/O takes time. If your application is doing a lot of it, you’d probably have much better results utilizing the time it takes to receive a response from the server or microservice to cater to other pending requests. Even if you think that your network is fast, for the code, it is a super slow process.

Take a look at this screenshot from a popular Github gist comparing the latency numbers of different operations that every programmer should know

Now to compare these on a humanized scale, these durations are multiplied by a billion. For accessing data from CPU memory on this scale, it takes a heartbeat; for reading something from SSD, it takes two days, and to send a data packet within the same data center over the network, it takes around six days.

Now imagine what all a human could do for those six days without waiting on the response. A network call is of the same magnitude for a piece of code.

This is where we need asynchronous I/O. It doesn’t mean making a single request run faster, but to enable a server to serve thousands of requests at a time as swiftly as possible.

Quoting from the documentation —

asyncio provides a set of high-level APIs to

- run Python coroutines concurrently and have full control over their execution

- perform network IO and IPC

- control subprocesses

- distribute tasks via queues

- synchronize concurrent code

Asynchronous programming is a big concept and out of scope for this article to explain in detail. Let’s look into one interesting example in which we’ll analyze the performance of popular requests library vs aiohttp with asyncio.

Here’s the gist which makes requests to a dummy API server’s different endpoints, once sequentially using requests and then using aiohttp in parallel. Let’s look at the results —

On average, for multiple runs, aiohttp with asyncio is 5–7x faster than sequential requests.

That said, if you take a look at the code of making asynchronous calls, it is much more complicated than using requests. This is a tradeoff you need to keep in mind, using only when needed because it increases code complexity and debugging could be another challenge in async code.

Data Classes

In simple words, data classes simplify the boilerplate overhead when you create data classes, aka models to represent the states and do operations on your data.

They implement the regular ‘dunder’ methods like __init__, __repr__, __hash__, __eq__ and so on automatically. Let’s take an example to see data classes introduced in Python 3.7(PEP-557) in action —

# Regular Data Class definition

class Order(object):

order_id: int

order_state: str

total_cost: float

def __init__(self, order_id, order_state, total_cost):

self.order_id = order_id

self.order_state = order_state

self.total_cost = total_cost

def __repr__(self) -> str:

return (f"Order Information for {self.order_id} -"

f"Order State = {self.order_state}, Total Cost = {self.total_cost}")

def __eq__(self, other) -> bool:

if not isinstance(other, Order):

return NotImplemented

return (

(self.order_id, self.order_state, self.total_cost) ==

(other.order_id, other.order_state, other.total_cost))

def __hash__(self) -> int:

return hash((self.order_id, self.order_state, self.total_cost))

# ------------------------------------------------------------------------ #

# With @dataclass decorator introduced in Python 3.7 all of this reduces to

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass(init=True, repr=True, eq=True, unsafe_hash=True)

class Order(object):

order_id: int

order_state: str

total_cost: float

# Dataclass decorator will automatically generate all the dunder methods

# It can also generate comparision methods and handle immutability.

Data class usage example

Exception Handling API Updates

There are several significant updates to the way exceptions are now handled in Python 3. New powerful features and a lot cleaner style for raising and catching exceptions have been added. Here are a few important ones —

- Python 3 enforces that all exceptions are derived from

BaseExceptionwhich is the root of the Exception hierarchy. Although this practice isn’t new, it was never enforced. - All the exceptions to be used with

exceptshould inherit fromExceptionclass.BaseExceptionto be used as a base class only for exceptions that should be handled at top-level likeSystemExitorKeyboardInterrupt - You must now use

raise Exception(args)rather thanraise Exception, arg— PEP-3109 StandardErrorno longer exists.- Exceptions cannot be iterated anymore. They do not behave like sequences.

argskeyword is to be used to access the arguments. - Python 2 allowed catching exceptions with the syntax like

except TypeError, errororexcept TypeError as error. Python 3 has dropped support for the former(PEP-3110). This was done because of typical mistake developers did to catch multiple exceptions like this —

try:

# do something

except TypeError, ValueError:

pass

# do something

except TypeError, ValueError:

pass

- This piece of code wouldn’t ever catch

ValueError; it’llcatchTypeErrorand assign the object to the “ValueError” variable. The correct way would be to use tuple likeexcept (TypeError, ValueError). - When you assign exception to a variable with

except TypeError as e, the scope of variable ends atexceptblock. From the documentation —

This is as if —

except E as N: foo

was translated to

except E as N: try: foo finally: del N

- This means the exception must be assigned to a different name to be able to refer to it after the except clause.

- Exception objects now store the exception traceback in

__traceback__attribute (PEP-3134). All the information about an exception is now present in the object. PEP-3134 also had a major overhaul to Exception Chaining. A detailed discussion on that will go beyond the context of this article so it is not covered here.

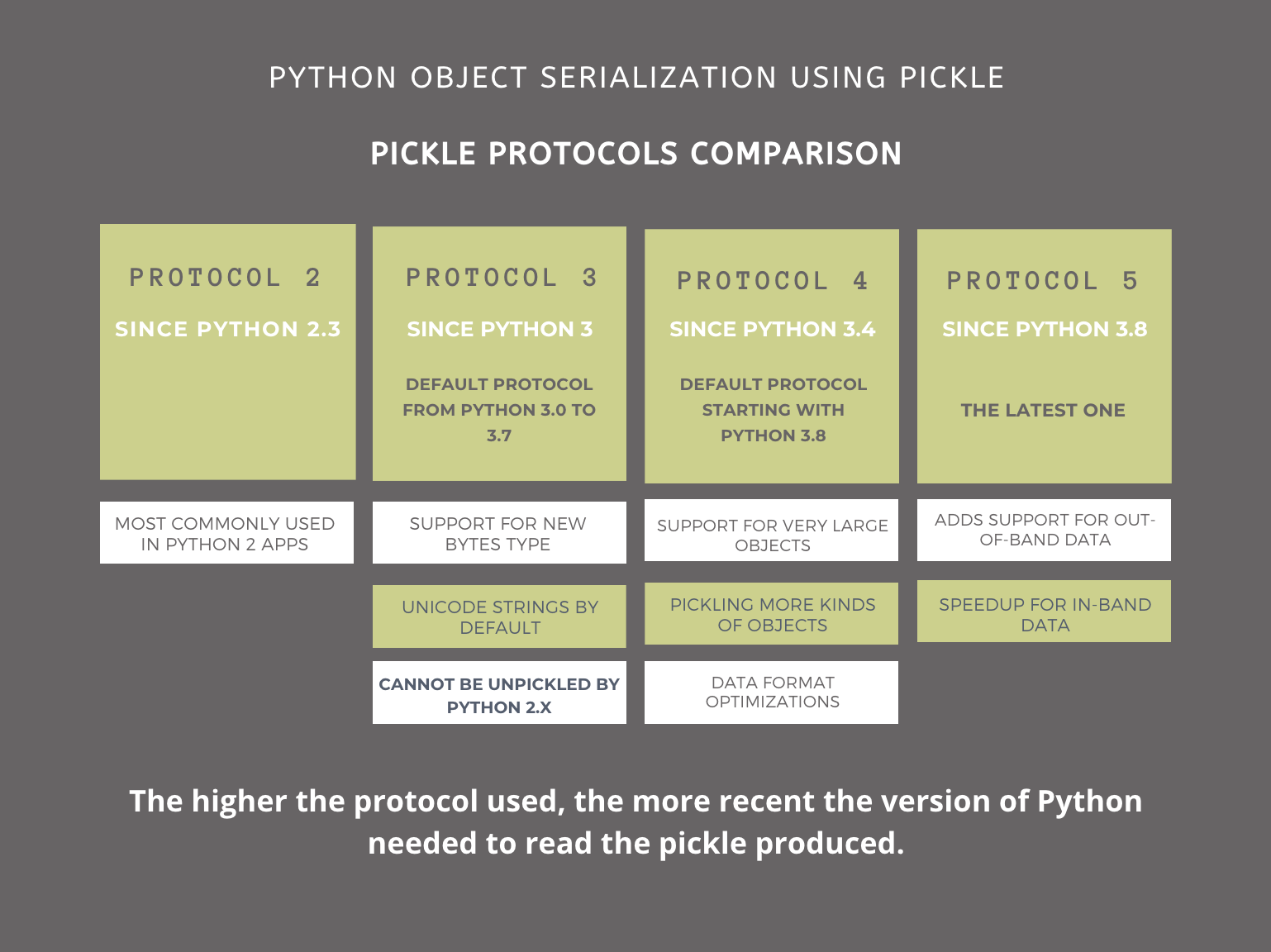

Pickling Protocols

pickle is a popular Python module known for serialization and deserialization of complex python object structures. Serialization is the process of transforming objects into a byte stream suitable to store on a disk or to be transmitted over a network. De-serialization is the opposite.

If you’re using pickle to serialize and deserialize your data in Python 2, you’d want to keep specific protocol changes in mind. Here’s a graphic listing the changes and compatibility guidelines —

Pathlib Module

Python 3.4(PEP-428) introduced the new pathlib module in STL with the simple idea of handling filesystem paths(usually done using os.path) and everyday operations are done on those paths in an object-oriented way.

From the release documentation —

The new pathlib module offers classes representing filesystem paths with semantics appropriate for different operating systems. Path classes are divided between pure paths, which provide purely computational operations without I/O, and concrete paths, which inherit from pure paths but also provide I/O operations.

Let’s take a look at a simple example using this new API

Enum Type(PEP-0435)

Python 3.4 release added an enum type to the standard library. It has also been backported up to Python 2.4, so chances are you might already be familiar and using it in the code. Normally, you’d create a custom class to define enumerations like this —

class Color: RED = "1" GREEN = "2" BLUE = "3"

With enum it’ll look like this—

from enum import Enumclass Color(Enum): RED = "1" GREEN = "2" BLUE = "3"

The difference between the two approaches being that enum metaclass provides methods like __contains__(), __dir__(), __iter__() etc. which aren’t there in a custom class.

Statistics(PEP-0450)

Python is also popular in the science and statistics fields. To acknowledge the importance, Python 3.4 introduced a new statistics module in the standard library to make scientific use-cases easier.

As the module documentation suggests, it is not intended to compete with libraries like NumPy, SciPy, or other professional proprietary software like Matlab. It is aimed at the level of graphing and scientific calculators. It provides simple functions for calculation of the mean, median, mode, variance, and standard deviation of a data series.

Secrets(PEP-0506)

Googling for “python how to generate a password” returns StackOverflow answers and tutorials, suggesting the use of random module whose documentation warns not to use its pseudo-random generators for security purposes. Developers may not go through the documentation or may not be aware of the security implications of using random to generate passwords and auth tokens.

This attractiveness of the random module became the rationale of the new secrets module added in Python 3.6. It provides the functionality to generate secured random numbers for managing anything that should be a secret. Let’s look at a couple of simple examples to create passwords and auth-tokens—

Standard Library Reorganization(PEP-3108)

Python’s rich standard library was extensively reorganized in Python 3.0. Many old modules were removed, many were renamed as Python grew to have a naming convention for them. The tools discussed in the following section can automatically handle most of these changes. Listing all of them will go beyond the scope of this article. PEP-3108 is the reference for all the STL reorganization changes.

New Syntax Features

- Print statement —

printis now a function, not a statement.

2. Walrus(:=) Operator assigns values to variables as part of a larger expression. Let’s look at this random piece of code in Python 2 and how it’s readability could be improved using assignment expressions in Python 3

3. Matrix Multiplication Operator(@) was introduced in 3.5 as Python advances towards making language better for scientific computations. Stating from Python 3.5 release documentation — currently, no builtin Python types implement the new operator. It can be implemented by defining __matmul__(), __rmatmul__(), and __imatmul__() for regular, reflected, and in-place matrix multiplication.

You could also use Numpy > 1.10, which supports the new @ operator. Let’s check out an example implementation of the same.

class Matrix(object):

def __init__(self, matrix_values):

self.matrix_values = matrix_values

def __matmul__(self, m2):

"""

https://docs.python.org/3/reference/datamodel.html#object.__matmul__

"""

return Matrix(Matrix._multiply(self.matrix_values, m2.matrix_values))

def __rmatmul__(self, m1):

"""

https://docs.python.org/3/reference/datamodel.html#object.__rmatmul__

"""

return Matrix(Matrix._multiply(m1.matrix_values, self.matrix_values))

def __imatmul__(self, m2):

"""

https://docs.python.org/3/reference/datamodel.html#object.__imatmul__

"""

return self.__matmul__(m2)

@staticmethod

def _multiply(m1, m2):

return [[sum(m1 * m2

for m1, m2 in zip(m1_row, m2_col))

for m2_col in zip(*m2)]

for m1_row in m1]

if __name__ == '__main__':

m1 = Matrix([[12, 34], [4, 2]])

m2 = Matrix([[2, 24], [12, 4]])

m1 @ m2 // Invokes the __matmul__ method

m1 @= m2 // Invokes the __imatmul__ method

def __init__(self, matrix_values):

self.matrix_values = matrix_values

def __matmul__(self, m2):

"""

https://docs.python.org/3/reference/datamodel.html#object.__matmul__

"""

return Matrix(Matrix._multiply(self.matrix_values, m2.matrix_values))

def __rmatmul__(self, m1):

"""

https://docs.python.org/3/reference/datamodel.html#object.__rmatmul__

"""

return Matrix(Matrix._multiply(m1.matrix_values, self.matrix_values))

def __imatmul__(self, m2):

"""

https://docs.python.org/3/reference/datamodel.html#object.__imatmul__

"""

return self.__matmul__(m2)

@staticmethod

def _multiply(m1, m2):

return [[sum(m1 * m2

for m1, m2 in zip(m1_row, m2_col))

for m2_col in zip(*m2)]

for m1_row in m1]

if __name__ == '__main__':

m1 = Matrix([[12, 34], [4, 2]])

m2 = Matrix([[2, 24], [12, 4]])

m1 @ m2 // Invokes the __matmul__ method

m1 @= m2 // Invokes the __imatmul__ method

Matrix multiplication @ operator implementation example

4. breakpoint() function was introduced in 3.7. It is just an easy way to enter Python debugger(PDB). It calls sys.breakpointhook() which in-turn imports pdb and calls pdb.set_trace().

You could also set an environment variable, PYTHONBREAKPOINT to enter the debugger of your choice.

To be continued…

The second part of this article explains automated tools, strategies, and some ideas on the role of testing in the process of migration. Part Two

Start a 14-day free trial with Scout to get key performance insights into your python application!